In previous posts, I defined a simple hierarchy for portraying the Enterprise and made a case for the importance of understanding and documenting the as-is Enterprise Architecture to a reasonable level of detail.

The As-Is Model

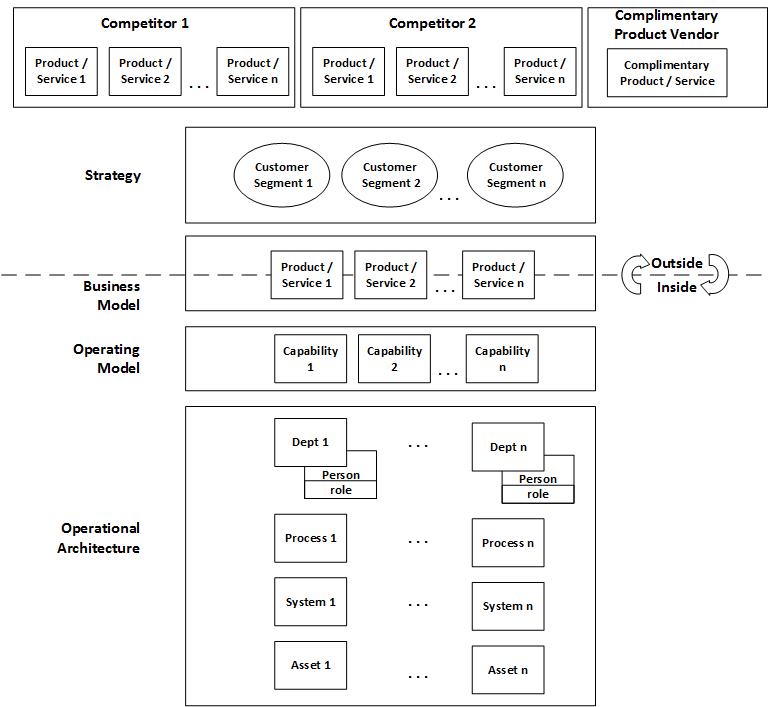

The diagram below portrays an enterprise and the ecosystem in which it competes:

Across the top there are two (of many) competitors, each of whom sell a number of products and/or services that compete with ours. At the right side of the top row, is a vendor that sells a complimentary product whose cost and value proposition can impact on the sales of one or more of the products or services we sell or which may be sold by other vendors. For instance, the price of gasoline or diesel fuel can alter the desirability of various models of automobiles.

In the next row are the customer segments and in the row below that, our enterprise’s products and services. The border between our enterprise and the competitive marketplace transects our offerings; that is, our offerings are the interface between our enterprise and the outside world. The customer segmentation model and our product and service offerings are intrinsic to our Strategy and Business Model.

The row below that is composed of the capabilities that we must enable to deliver our products and services. This is our Operating Model.

The final row contains the elements of our Operational Architecture—People (organized into departments and roles), Processes and Technology, frequently abbreviated ‘PPT’ in EA-speak. I have included Assets in the Operational Architecture as they are frequently dedicated to other elements of the PPT configurations supporting various capabilities. For instance, factory buildings may be assigned to specific manufacturing capabilities.

As mentioned previously, this is a multi-dimensional model. Entities in this schema can be connected many-to-many. For instance, an ERP system can support multiple work processes in the Order-to-Cash business process for a number of our products or services. People and departments can be assigned to multiple processes and therefore to multiple capabilities. Similarly, products or services may overlap in their connection to multiple customer segments. I have not attempted to portray links among the elements of this diagram because they would quickly overwhelm it.

Ideally, the model should represent the entire enterprise, however, this is not absolutely necessary and may not even be possible in the case of a larger multi-national conglomerate. Attempting to expand the model scope beyond entities common among relevant business units may be excessively labor-intensive, costly and can actually make the end result less useful.

Discovery: Vertical and Horizontal Slices of the Model

With the model in place, it should be reasonably easy to trace Value Chains—the sequential path of processes from the beginning of a business process to the end. Alternately, a horizontal section through the model may reveal all of the Value Chains in which a specific entity appears or in which redundant instances of similar entities appear.

In the previous post, we posed a number of questions about our auto business:

- How many different CAD systems do we have?

- Who is using them and for which of our vehicles?

- How much do they cost us?

- Can we decommission some of them, consolidate our users and save some expenses?

With the as-is model in place, we are now equipped to answer the first two questions, which will put us on the path to answering the second two.

We also asked:

- If we want to make a new line of vehicles can we take a slice of our existing enterprise capabilities and re-purpose them for that?

- What would be involved?

- How would we fill in any gaps this might leave in our existing operations?

- What are the risks and costs?

Again, the as-is model is an excellent starting point for tackling at least the first two questions in this set, as well.

I will reiterate a point I made in the previous post—if you do not have the as-is model and are faced with an opportunity or a threat, then the first step in determining a response is to create at least as much of the model as is necessary to evaluate alternatives. It costs time and effort to create and maintain the model, but that must be weighed against potentially limited data quality and delay resulting from trying to create it under pressure in a moment of need.

Inside-Out vs. Outside-In

Desires to transform may emanate from new or increased capabilities, which can lead to new or improved products or services (inside-out) or from developments in the marketplace that necessitate a response (outside-in.) In either case, the enterprise must trace the value chain supporting any product or service that may be impacted by a transformation in order to assess its costs and benefits comprehensively. For example, if a competitor sets a new, lower price point for one of its competing products, the enterprise must evaluate all of the opportunities to wring cost out of the value chain and assess what, if any, impact each prospective change might have on other model elements and value chains. Or, if a new technology creates an opportunity to add features or quality to a product but will necessitate transforming the production process in a way that creates a temporary redundancy until other products can be migrated, what is the cost-benefit impact of that? What are the risks involved?

In a healthy company, transformational initiatives should emanate as much from opportunities to add or improve capabilities (inside-out) as from threats or opportunities coming from the marketplace (outside-in). Such resonance is much easier to support when it’s possible to trace and understand the operational impacts comprehensively.

To-Be and Portfolio Management

Given the enterprise’s competitive situation, including trying to surmise relative strengths and weaknesses between its own and competitor’s capabilities, it must determine what initiatives to pursue to maintain and improve its lot. Initiatives may involve selling all or part of the company, entering a new line of business or investing in increased capacity for some capabilities, for instance.

Prospective transformation initiatives should be assessed and maintained in a pool. Each of the initiatives is in competition with the others for funding and all should have a pro-forma cost, benefit and risk analysis attached. Ultimately, a subset of the initiatives will be funded, based on the needs and preferences of the enterprise. The to-be model of the enterprise, then, consists of the current as-is plus transformations resulting from the portfolio of all approved initiatives.

What initiatives belong in the pool? How many initiatives belong in the pool? It depends.

The candidate initiatives list begins with all plausible developments that may present threats or opportunities for the enterprise that will require a response and is refined to eliminate those that are very unlikely or which will have little impact. Of those that remain, it may be necessary to represent multiple variations of some. For instance, the price of oil is a determining factor for many businesses. What these businesses must do to position themselves in response to changing oil prices may be different in each different price range, and might be represented by a number of different initiatives.

How much time and energy should be spent evaluating the initiatives in the pool? Again, it depends.

For the least likely, the least well-understood or the least impactful, it may be adequate to merely note the remote potential to need to drill into detail at some future point. For others that are more tangible and immediate, more attention is warranted.

Besides developing tactical plans, there is a strategic benefit to building, studying and pruning the tree of possibilities—discovering strengths and weaknesses. In evaluating the scenarios, it is likely that themes will begin to emerge, such as that existing processes and enabling systems would impede scaling up to increase capacity in some area, creating opportunity costs if the markets for the products they support were to suddenly grow.

As you would expect, having an as-is model and prospective initiative pool in place facilitates the initiative selection and portfolio management process. Among other things, they should provide a structure and format for analyzing and presenting information about prospective transformation initiatives that can facilitate the assessment and evaluation process.

Who Maintains the Models?

EA, in conjunction with whomever in the enterprise is responsible for strategy or planning should maintain the models but they must be contributed to by a wide range of other people. In the next post, I will explore the roles of Enterprise Management, EA, the Project Management Organization (PMO) and ICT with respect to options that can impact on organizational effectiveness.