Much has been written about the use of the terms “risks” and “opportunities” with respect to the process that PMI refers to as “Manage Risk.” A recent thread on the subject of the terms on LinkedIn has drawn over 100 responses debating their meaning and usage, dissecting them in detail and resolving little. For the purposes of this post, let’s agree to refer to outcomes of planned project activities as uncertainties.

THE PROJECT MANAGEMENT INSTITUTE RISK MANAGEMENT PROCESS

The PMI risk management methodology defines the result of each activity as normally-distributed, implying that it is symmetric with respect to the projected mean. Think bell curve. While this may not be completely accurate (many project activity outcomes may actually be better described by other, asymmetric distributions) it is certainly adequate for the use which is made of it in the course of establishing project scope, time and cost baselines. What is important is that (a) there is a probability of fluctuation both above and below the mean and (b) the impact of the fluctuation may be either negative (a “risk”) or positive (an “opportunity”) for the project. Management of uncertainties, then, involves avoiding, mitigating, transferring or accepting the probability of negative outcomes and also increasing the probability of achieving positive ones.

The PMI methodology is intended to address a wide array of project types and therefore there is a limitless array of activities, with attendant dependencies that may be included in a project and which should be addressed by the Risk Management process. For instance, pouring concrete may be an activity with uncertain outcome on a construction project while establishing a messaging architecture may be part of building a trading application.

For the purposes of this post, we will focus on technology implementations as an example, though the issues addressed in it are universal to the management of all projects.

PMI MANAGE RISK

The first step in the PMI Manage Risk process is to identify all the possible uncertainties in a project plan; easy to say and not so easy to do. The PMI recommends polling as many sources as possible, including panels of experts and historical information from previous projects, to accumulate a superset list and then cull the applicable ones from it. While starting from an established list will be somewhat helpful, differences between projects, even similar-seeming ones, can limit the value of the leg up this can provide. If, in fact, it results in less time spent considering the specific characteristics and circumstances of the project at hand in favor of mindlessly cherry-picking entries off the list, then it can be detrimental to the process.

How then, should PMs identify the relevant and meaningful uncertainties on which to focus the majority of the Manage Risk effort? Can we define a systematic approach that will make this process more efficient and comprehensive?

Focus and Relevance

The PMI project management lifecycle has five process groups (phases)—Initiation, Planning, Execution, Monitoring and Controlling and Closing. The Initiation process group deals with the project at a very high level and results in a conceptual definition and rough (+/- 50%) budget. The Planning process group results in a detailed definition, work plan, budget and schedule. The list of uncertainties to be addressed that is produced in Initiation will become much more focused in the course of Planning.

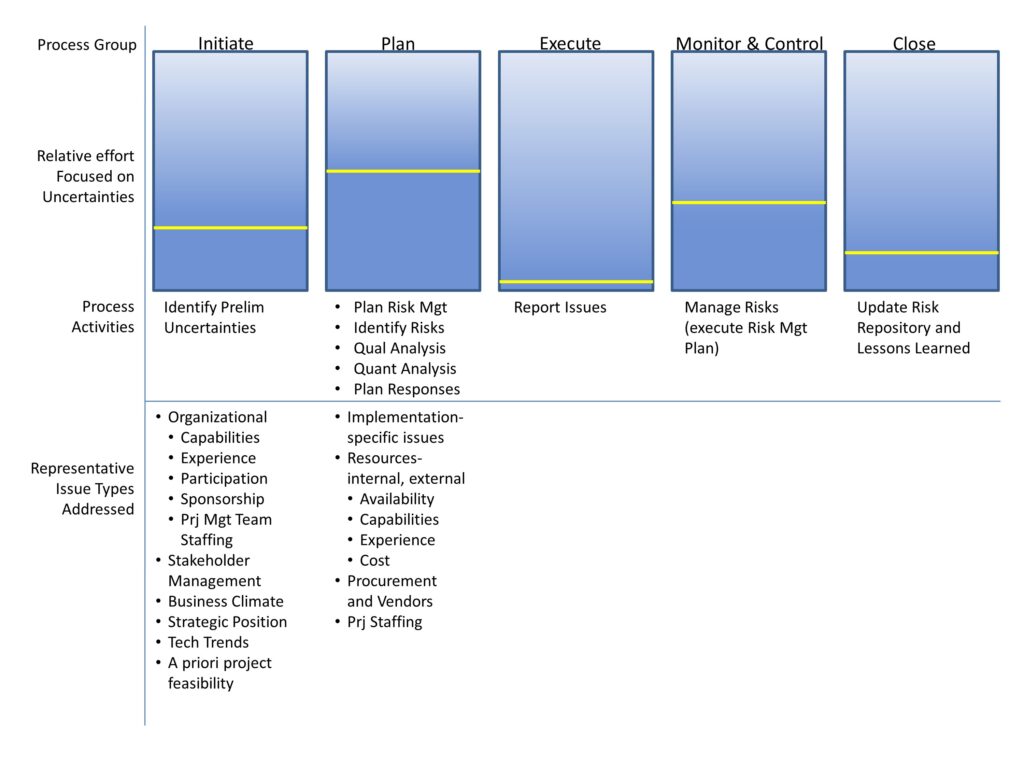

Risk Management should occur throughout the project lifecycle, with its own process superimposed on the overall lifecycle. The PMI Risk Management process includes (a) Plan Risk Management, (b) Identify Risks, (c) perform Qualitative Assessment, (d) perform Quantitative Assessment, (e) Plan Responses and (f) Manage Risks. The earlier steps in the Manage Risk process (a through e) occur in the Initiate and Plan process groups, before project execution begins. Manage Risks, monitoring for occurrences of fluctuations requiring action and executing planned responses, occurs during the Execute and Monitor and Control process groups. However, changes to the project plan, adoptions of fallback processes or impacts of uncertainties can all necessitate iteration of the Risk Management process, updates to the list of uncertainties and re-analysis and formulation of new responses at almost any time during the project.

Without question, the entire Manage Risk effort should be prioritized on the uncertainties that affect the desired overall project outcome most directly. But what is that? The PMI project management lifecycle dictates the production of several artifacts that should contain information to help focus the Identify Risks effort.

The Project Charter should include a Business Case for the project, overall project constraints and requirements and a list of assumptions. The project business case describes why the project is being funded and what is expected to be achieved. The project constraints cover such issues as deadlines, cost limitations, minimal functional and performance requirements and so on. Assumptions may consist of anything relating to the execution of the project.

MANAGING THE TRIPLE CONSTRAINT

This information should provide a basis for establishing precedence among Cost, Time and Quality or Functionality—the Triple Constraint. For systems implementation projects, it is axiomatic that decisions to change one of the three will impact either or both of the other two. For instance, accelerating the project’s delivery may involve adding staff (increasing costs) and/or decreasing functionality. Understanding the sponsor’s preferences will provide focus as to which uncertainties to prioritize.

Stated assumptions are frequently direct indicators of high-priority uncertainties. It is quite common for people working to define a project at its outset to incorporate issues about which they are unsure in the form of assumptions. For instance, “we assume that software component A can be integrated with software component B via mechanism C.” Evaluating assumptions and planning to deal with the impact of their proving to be incorrect should be undertaken as early in the project planning process as possible.

The framework specifies additional knowledge areas that can be useful to identifying uncertainties, each of which has specific tasks and deliverables associated with it. In addition to managing Scope, Cost and Time, these include Quality, Communications, People and Procurement. Each of these areas should be considered to uncover additions to the inventory.

The diagram, below, shows each of the lifecycle process groups, indicating the relative effort expended on Risk Management within it and showing the steps in the Manage Risk process that are part of each. The bottom half of the chart lists the types of uncertainties that are more in focus in each process group.

Notice that in the Initiation process group we are focused on Organizational, Business and Strategic issues that relate to the context in which the project will be executed. We want to assess what the level of support for the project is and how contentious its implementation is likely to be and identify whether issues resulting from this are likely to impact the project. We need to have some idea of what technologies and techniques we might use to implement the project and whether the organization has experience and expertise with them. We also need to make a preliminary assessment of anything that may adversely impact the project’s feasibility. We are also quietly creating preliminary strategies as to how we will immunize the project from potential negative influences.

From the standpoint of identifying uncertainties at this early stage of the project, an existing list of areas to consider is worthwhile but is not likely to be particularly applicable at a detailed level unless you have worked in the organization previously and have good knowledge of the business, people and processes. Nonetheless, here is where your uncertainties inventory must start to establish the hierarchy of concerns into which it will ultimately develop

So, at this point we should have a preliminary list of uncertainties to be addressed based on (a) an understanding of the sponsor’s requirements, constraints and preferences, (b) specific identified areas of uncertainty, derived from the documented assumptions and (c) prospective uncertainties we have identified by considering the individual knowledge areas of the methodology. However, we are left with a problem—we do not know at this point how each of the execution uncertainties may actually relate to the specific customer priorities. Will not having in-house staff with expertise to build certain components impact the quality effort? If we force our QA team to share the development infrastructure with the developers could that impact our delivery date?

WHAT’S NEXT?

The next post will address the expansion and refinement of our uncertainties inventory through the planning phase of the methodology and future posts will deal with how we can define a structure in which to maintain the information we accumulate so as to facilitate its reuse on future projects.